Please note that this blog was originally published in February 2020.

Breaking the Barriers in supporting women and girls affected by harmful practices such as female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C).

Alima Dimonekene, Hestia caseworker and trainer and FGM activist and leading voice in the call for changes around services for survivors.

Today is Zero Tolerance to FGM Day on the 6th February. A commemorative day made possible by incredible women and men from Africa in 2003. It is important to reflect on the massive successes in addressing FGM in the UK.

What is FGM?

FGM has been described, and sometimes perceived, as a rite of passage, celebration or ceremony when a girl reaches maturity and can be considered a real woman. The causes of female genital mutilation include a mix of cultural, religious and social factors within families and communities. The practice often leaving women and girls with lifelong health complications and risks to life.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines FGM as:

“…all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” (WHO, 2014).

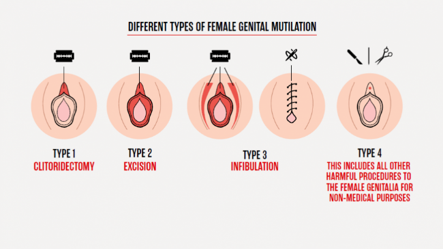

There are 4 main types:

Type 1 (clitoridectomy) – removing part or all the clitoris

Type 2 (excision) – removing part or all the clitoris and the inner labia (the lips that surround the vagina), with or without removal of the labia majora (the larger outer lips)

Type 3 (infibulation) – narrowing the vaginal opening by creating a seal, formed by cutting and repositioning the labia

other harmful procedures to the female genitals, including pricking, piercing, cutting, scraping or burning the area.

FGM is often performed by traditional circumcisers or cutters who do not have any medical training. But in some countries, it may be done by a medical professional.

In 2014 I reached a pivotal moment in work in tackling FGM when I was asked by the government to open the first global Girl Summit aimed at rally domestic and international efforts to end female genital mutilation (FGM) and child, early and forced marriage (CEFM). The then former Prime Minister David Cameron pledged and committed that the U.K. will do all it can to end FGM by 2030.

A commitment that continued with former Prime Ministers Theresa May and Boris Johnson.

Where are we now

Over the year’s survivors of female genital mutilation/cutting struggled to access services across London and the home counties. However, with the introduction of early intervention approaches, like the Pan London FGM Initiative which aimed to examine ways to prevent FGM among women and girls, a new wave of funding has emerged that seeks to increase support and services catering to the welfare and wellbeing of women affected by FGM.

Despite some challenges around the funding or the lack of it, campaigners and activists like myself have found unique ways of mobilizing awareness and confidence in our communities.

Services on offer

Sadly, due to cuts to services, many nonprofit and third sector organizations struggle to provide the vital essential support and advocacy so desperately needed by women affected by FGM. In many cases women complain about inadequate advice and support offered at a time when they most need it.

However, organizations like Hestia are changing the way services are provided for women affected by FGM. From floating support to empowerment groups, Hestia offers both affected women and their communities access to specialist services.

What can communities do to support women and girls already living with FGM?

In breaking the barriers in supporting women and girls affected by harmful practices such as female genital mutilation/cutting, communities voices are vital. Communities must engage in the fight to protect and safeguard girls at risk, whilst also helping women already living with the effects of FGM, by demanding more therapeutic care and supporting adult services in their own communities.

Research shows that, “if practicing communities themselves decide to abandon FGM, the practice can be eliminated very rapidly”. In 2007, UNFPA and UNICEF initiated the Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting to accelerate the abandonment of the practice. See more here

What we do know is, through the incredible voices of survivors and campaigners such as Hawa D Sesay of Hawa Trust Hackney, Hibo Wardere of Waltham Forest, Sarata Jabbi of Birmingham and Mama Sylla of East London, the services catering to women affected by FGM and other forms of harmful practices services are now improving.